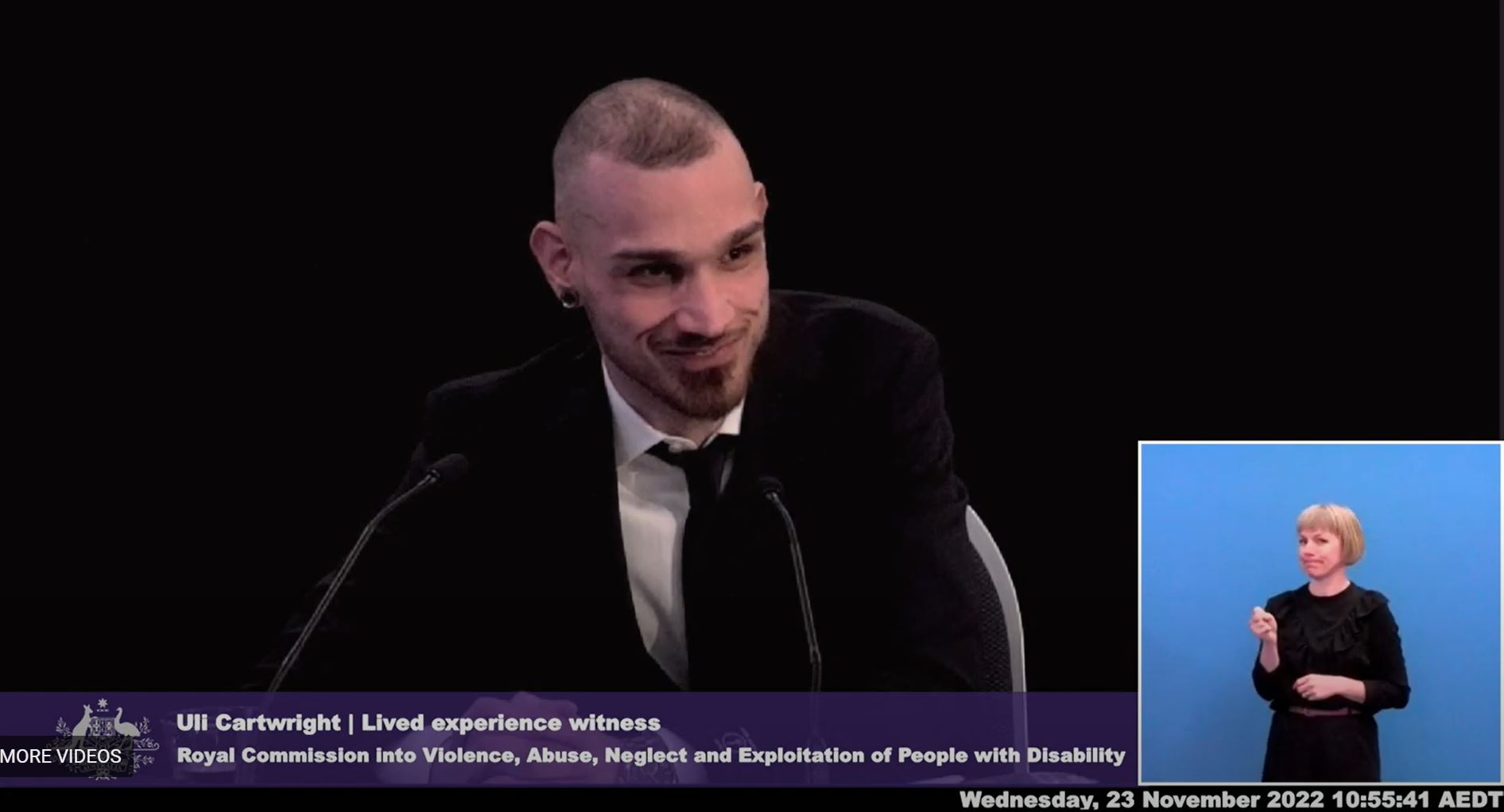

Uli Cartwright is a young man and self-advocate from Melbourne, Victoria who works with VALID.

On 23 November, Uli appeared as a witness at the Disability Royal Commission in Sydney to talk about his experiences of Guardianship.

After his appearance, Uli talked with Inclusion Australia about decision making and guardianship, what it was like to share his story with the Disability Royal Commission and his advice for other people with a disability who might be thinking about speaking up.

Hi Uli, thanks for talking with us. How do you explain guardianship to other people?

Guardianship is something there to protect somebody from being vulnerable and reinforce their human rights. Enable them to engage in society with support and to do that safely, really.

So why was guardianship a problem for you?

Because I had an intellectual disability, so it took a little bit longer for me to understand. It took me a little bit longer to get the hang of things.

Then I had the normal factors of being a teenager and growing up on top of that. I had intellectual disability and teenage hood collide. I thought I was Superman, and I could do everything. I was getting myself into debt and I didn’t understand the responsibility that I had to myself and to other people.

Guardianship became more than about money than for you, didn’t it?

I feel like that my guardianship order was used to discipline me and restrain me because I didn’t have the education or the practical skills to pay my bills or understand what paying my bills meant and when I didn’t want to listen. That’s why I sit and reflect what guardianship really means, because it’s meant to protect people, not be used as a weapon.

What are some of the ways that you felt disciplined?

As I said on the stand, I just got stripped of my identity. You can’t really buy much with $50 a week. You have to choose to buy undies or a video game. You can’t buy both. In normal society you have the right to buy what you need and also what you want. I had to choose one of them and then the money was gone. I couldn’t go out on a date. I could go to the movies maybe, but I couldn’t get a drink. Just very basic stuff that anyone else would do.

Once that money was gone, I couldn’t do anything. So, my life became very structured, very rigid – “this is what I can do, this is what I can’t do.”

How did it feel to have other people making decisions about your life?

Very frustrating at the time because I lived in foster care, and I was a teenager and just wanted to rule life and do what I wanted to do. The people that were looking after me at the time was very much like “alright, it’s out of our hands now” but it just felt more and more institutionalized like that, they were trying to force me to conform. It just got worse and worse. It doesn’t matter what I said. They had the final say. They had total control. More hindrance, more intrusive, more difficult, more bureaucracy, more loopholes, just more everything.

Why was it important for you to Share your story with the Royal Commission?

Because the simple fact is guardianship and administration orders aren’t used the way they’re meant to be used. They’re using it to grab power and silence people. Whoever’s in charge can get away with whatever they want.

If it’s used correctly, I have no qualms about it. There is a place for guardianship. But 80% of the time I feel it is used as grabbing power.

Even if guardianship is needed, the people that administer it – even if they’re doing a good job – they still act like they are in charge and they make life difficult. It’s not executed in a way where it’s inclusive for the person. It’s just not done right.

So, even when guardianship orders are needed, there’s a lot that they can do to make it a lot more inclusive and involve the person.

Yeah. We are not at the table. They just do it for us. They’re in charge and they use those laws and their thoughts and their perceptions. There’s no will and preference, basically.

What do you hope will happen because of your appearance at the Royal Commission?

Well, I’ve got some great feedback and I’m honoured. I’ve had a few people come to me and say, wow, I didn’t know people in the government could exert that much power. So firstly, I brought the issue to the forefront.

And now there are organisations like Inclusion Australia, Villamanta Legal Services, the Office of the Public Advocate. Now they can point to [my testimony] and they can talk about it. I’ve done my bit. If I need to step back into the ring, then I will. But I’ve done my part and brought it to the attention, the door is open.

As I said to the Commission, I’m here, I’m staying and I will do with everything in the book. There are people that have this industry and this culture and use the book against people. I will do it the right way for the benefit of everyone else.

What was it like talking to the Commissioners?

Terrifying! I was terrified, but not because it was scary. I think it was terrifying because I understood the responsibility. I had heard stories that this stuff happens, and I was like, wow. I went the State Trustees, the Victorian Ombudsman’s report, Interstate trustees and, like, just looked around and I’m like, holy moly, this is a big issue. It just goes to show how big of an issue it is.

I also treated the Commissioners and the lawyers like humans. As you may know, if you watched, I thanked them. I appreciate their work. I reminded them that, you know, they’re doing the best they can. They’ve been doing it for three years.

How did you feel when it was all over?

I felt like holy moly, I did that. Everything that I prepared for – I didn’t even open my scrapbook. I had three pages of notes, but I just spoke to Miss Eastman, the lead Counsel, and it just came out. It wasn’t prepared!

The most proud moment was when I looked to my lawyer. She smiled and didn’t say anything. I’m like, alright cool, legally I’m safe. But then I met a few advocates from NSW that were crying and saying thank you. I don’t know their story. I don’t know what they connected to, but if they’re smiling and they’re happy, then I must have done something right. It’s not about me.

People of are anxious about sharing their story. What advice would you give to people about sharing their story with the Royal Commission or with things that happen in the future?

You have a voice. Understand what you can and can’t do. Do it properly, because if you do it correctly, I feel like you would feel proud by the end of it. You’ll feel satisfied. The reason why I wore a suit wasn’t to look good. It was to show the public and the Commissioners that may not have done me right, that I am equal. I can look presentable. I can contribute to society.

At the end of the day, the Royal Commission has been doing it for three years and I genuinely in my heart feel like they care about what we think – not what support workers think or what the government thinks. They’re there for us. Try it. If it doesn’t work, that’s fine. At least you tried.

It’s OK to ask for help. If the person that you asked doesn’t want to help you, that’s fine. Ask someone else. I had lots of support to get to that one moment. Six months of work, lawyers, Inclusion Australia, logistics teams to fly me there and back. A lot of writing – I really don’t like writing, I was terrible at school, but it doesn’t matter how you need to get there. It doesn’t matter what requirements you have or how you do things best. If you want to do it, do it. Be ambitious but do it the right way.

Don’t be destructive. Work as a team and ask for help. Reach out to people and the more noise the better!